Stanford study shows significant benefits when mental health clinicians and police officers respond to 911 calls

Researchers from the Gardner Center spent two years studying a co-responder pilot program in San Mateo County, finding meaningful reductions in involuntary psychiatric detentions.

911 is usually the first phone number we call in an emergency — but what if that emergency involves a mental health crisis? That's the challenge police departments have been grappling with as mental health disorders continue to rise in the United States, especially among young people.

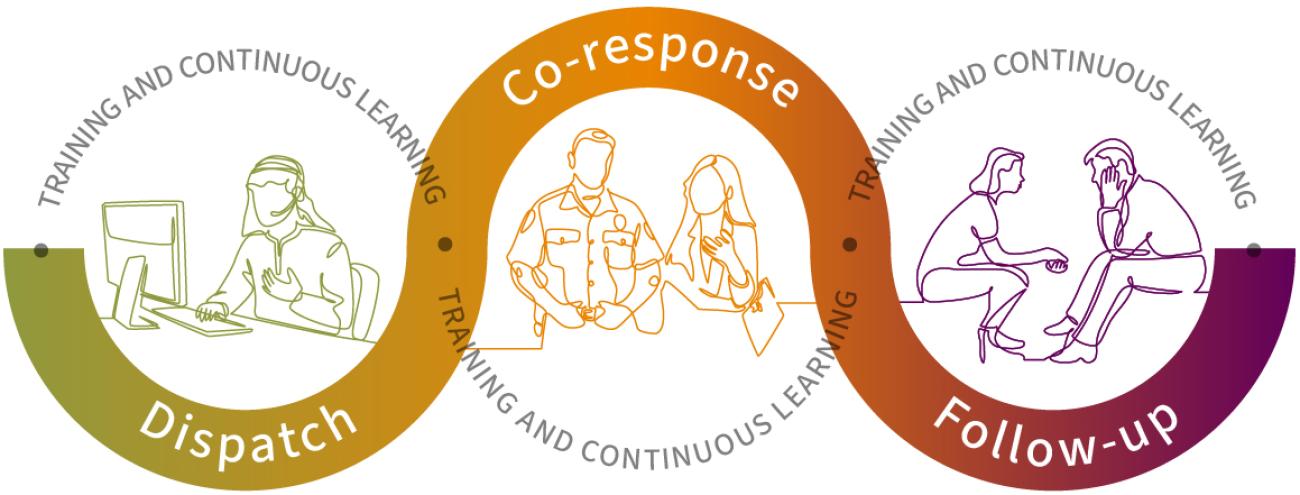

Cities and counties across the country have been experimenting with new models to address this challenge, including California's San Mateo County, which launched a Community Wellness and Crisis Response Team (CWCRT) Pilot Program in four of its largest cities starting in December 2021. The program provides a mental health clinician co-responding with a law enforcement officer to 911 calls that involve someone experiencing a mental health-related crisis.

The county also engaged Stanford's John W. Gardner Center for Youth and Their Communities to conduct an independent evaluation of the pilot program's implementation and outcomes. This effort on the part of the Gardner Center has culminated in the production of six written reports now available to the public and the first credible causal estimates of a co-responder program’s effects on communities in the United States.

Noteworthy community benefits

The researchers found that the program reduced the number of involuntary psychiatric detentions (or “5150” holds) by 16 percent in participating communities and the number of calls for service recorded as “mental health incidents” by 17 percent.1 Meanwhile, the types of calls prompting dispatchers to request a co-responder team rarely resulted in an arrest, use of force, police case, or criminal complaint — so the presence of the program did not have any detectable impact on these outcomes at the community level.

Reports in This Series

Implementation Reports

Background Reports

"It is rare that we see effects of this magnitude when studying a program with credible research designs," observes Thomas Dee, faculty director for the Gardner Center. "This is really good news for agencies that want to find new and cost-effective ways to better serve some of the most vulnerable members of their communities."2

Dee and Gardner Center researchers based their findings on data from the first two years of the pilot program’s implementation (December 2021–December 2023). The team collected and linked dozens of administrative datasets across nine police agencies, including data from participating police agencies in Daly City, Redwood City, San Mateo, and South San Francisco, as well as nonparticipating (i.e., comparison) police agencies.

Beyond the numbers

These numbers tell an important story, but equally powerful are the experiences of the dispatchers, clinicians, and officers involved in the pilot program, as well as adjacent organizations (e.g., staff of local schools, psychiatric emergency rooms, city and county government, and nonprofit organizations).

The Gardner Center team also invested significant time and energy to document how the program was implemented, conducting over 60 interviews and 30 observations (including police ride-alongs and dispatch sit-alongs) and reviewing more than 50 program-related documents. They found a story of cooperation and learning that had important benefits like:

- A sense of safety for clinicians after officers secure a scene, so they can work directly with individuals in crisis and their loved ones;

- Meaningful connections to community mental health resources so individuals can get the support they need to prevent future crises;

- New approaches and language that police officers learn and use even when on calls without a clinician;

- Improved documentation for emergency room staff when admitting an individual for psychiatric care;

- Support for school administrators who are not equipped to handle safety and mental health emergencies in schools.

These qualitative research efforts provide important insights about what factors helped facilitate the program's effectiveness; opportunities for improvement as San Mateo expands it to additional municipalities; and considerations for other counties interested in adopting similar programs.

Research rooted in partnership

Perhaps it goes without saying, but this kind of long-term, in-depth research requires a profound level of trust and transparency among program partners, as well as an openness to the research findings, whatever they may be. "That kind of trust doesn't happen overnight," says Gardner Center Executive Director Amy Gerstein.

She explains that the Gardner Center has a long history of working with San Mateo County, from studying the effects of homelessness on teens to working with school districts to improve support for English learners. "This is what we call community-engaged research — conducting research in the context of long-term, trusted partnerships — and it's the platform that enables us to do meaningful work close to home and beyond," says Gerstein.

"That’s why the County of San Mateo engaged the Gardner Center when it planned to embark on this new idea," says Jei Africa, director of the county's Behavioral Health and Recovery Services, a key partner in implementing the program. "It’s critical to have trusted researchers to help understand the impact of our efforts, especially highlighting not only what worked but also considerations for improvement."

A path forward

The Gardner Center will continue its study of the CWCRT program in San Mateo County as it is rolled out to six additional municipalities in the coming year, and has also received funding to study the use of co-responder programs nationwide.

“This is important work,” explains Dee, “because communities have had little evidence to guide them even while alternatives to traditional emergency response systems have proliferated across the country. The causal evidence we have been able to present adds to a nascent, yet growing, body of evidence on alternative emergency response programs, which can help communities understand how mental health co-responder programs can benefit both individuals in crisis and their communities at large."

1. Section 5150 of the Health and Safety Code provides legal authority to detain a person involuntarily for assessment, evaluation, and treatment “when a person, as a result of a mental health disorder, is a danger to others, or to themselves; or is gravely disabled due to a mental disorder,” defined as being unable to provide for their own basic needs such as food, clothing, or shelter.

2. Prior work by Thomas Dee and Jaymes Pyne showed benefits of a mobile crisis response program in Denver.